Intro

One of my favorite machine learning papers is called Pattern Recognition in a Bucket. While it’s not widely known, it is a flashy introduction to the field of reservoir computing. The paper proposes a unique way to train a neural network and doesn’t take itself too seriously along the way. This post is about Pattern Recognition in a Bucket: come for the Liquid Brain, stay for the unintuitive approach to neural network training.

Background

Recurrent neural networks are hard to train, especially if you don’t have GPUs and autograd software. In the early 2000s Torch had just been released, GPUs were orders of magnitude weaker than they are today, and the best way to train recurrent neural networks was still up for debate. A couple groups found some success by cutting this Gordian Knot. They said, “if training RNNs is hard, then just don’t do it!” More precisely, they came up with the idea of liquid state machines and echo state networks. These papers point out that if you have enough untrained recurrent units acting as a reservoir of potential functions, then you can simply train a linear function of their outputs to solve your problem of choice. Collectively, this framework is now referred to as reservoir computing.

Interestingly, the Liquid State Machines paper doesn’t limit itself to only using recurrent units. The authors show that the output of any dynamic system that meets certain requirements (glossed over here) can be fed into a linear layer and used to learn things. Fernando and Sojakka, the authors of Pattern Recognition in a Bucket, read the Liquid State Machines paper and said “You know what’s a liquid? Water!” They then set out on the quest to to train a neural network1 with a bucket of water.

Highlights of Pattern Recognition in a Bucket

Methods

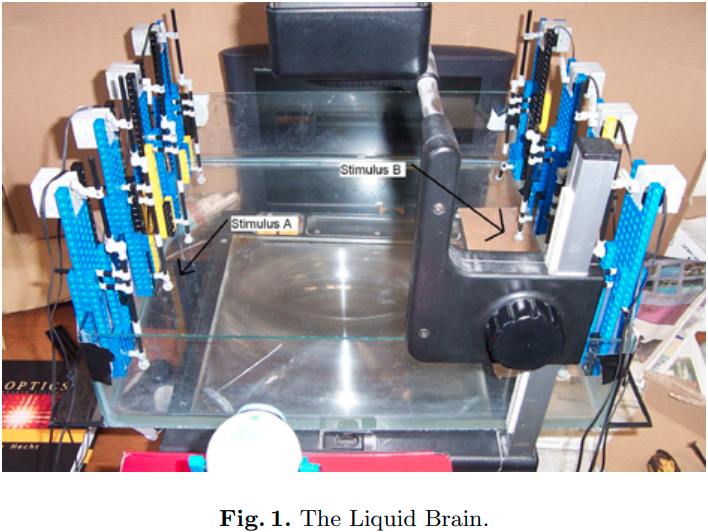

To feed inputs into a reservoir, the authors used a set of motors to create waves in a tank of water (shown below). The output was created by shining a light through the water onto cardboard, taking a video of the cardboard, running a filter over the output, then feeding the resulting pixels into a perceptron.

This figure is one of my favorites in any paper I’ve read. It’s hard to beat a plastic box covered in LEGO motors with arrows drawn on in MSPaint. The caption “The Liquid Brain” is just the cherry on top2.

Experiments

As a proof-of-concept, the authors first used their Liquid Brain to solve the XOR problem. For context, XOR is a simple binary classification problem where you return 1 if both inputs are 0 or 1, and 0 otherwise. XOR is a good toy problem, because it’s easy to solve with a nonlinear system (or just an extra input dimension), but impossible to solve with a linear model. The complexity of the liquid state machine is overkill for solving XOR, which the authors acknowledge by saying “Our approach of adding an extra 700 dimensions is to use a machete to garnish canapes.” Mostly the XOR experiment is there to show that the model actually works.

To show that their system would work on a more challenging problem, Fernando and Sojakka then went on to tackle speech recognition. More specifically, they convert the waveforms of an individual saying “zero” and “one” were converted to motor frequencies via a flavor of Fourier transform. This process was repeated for 20 iterations of each word, and the results were fed into a perceptron. Surprisingly (to me at least), they managed to get ~99 percent training accuracy as opposed to 75 percent accuracy when training the perceptron on the raw input.

So What?

Like most papers, Pattern Recognition in a Bucket did not spark an “ImageNet Moment”. People still use reservoir computing, but the field lies far off the beaten path of machine learning research.

However, despite being less well known than more mainstream approaches, ideas from reservoir computing show up frequently in deep learning research. For example, the idea that a neural network has useful functions baked in at initialization time is at the core of the Lottery Ticket Hypothesis. Similarly, Rosenfeld and Tsotsos found that the final layer isn’t special: you can train a random subset of weights in a neural network and still get good performance.

I believe all these papers3 are approaching the same phenomenon from different directions. Something to do with the large number of functions that are represented at initialization, or the dynamics of neural network training, or some aspect of random matrix theory, causes neural networks to be robust to lots of modifications that intuition says should break them. It will be interesting to see what the future holds for these areas of research, and whether they eventually converge.

Interesting Historical Notes

-

Back in 2003 when Pattern Recognition in a Bucket was first published, a high end graphics card would set you back 250 dollars and have ~ 10 shaders. Today’s top of the line graphics card has ~10000 shaders for a price of around $20004.

-

This review paper is fascinating. It shows that there are many potential ways to make neural networks work, and that it was not at all clear in 2007 that autodiff + backpropogation + GPUs + large datasets would be the dominant paradigm.

Footnotes

-

It’s technically a liquid state machine, but I’ll count it because LSMs are typically done with neural network layers. ↩

-

I miss showy method names like “The Liquid Brain”, “Neocognitron”, or “Perceptron”, though modern names are also pretty good. ↩

-

As well as papers about pruning ↩

-

The price fluctuates by ~50% based on semiconductor tariffs, cryptocurrency demand, and profiteering due to the small supply. ↩