Intro

Designing machine learning (ML) experiments to solve biological problems is difficult because it requires expertise from multiple fields. On one side, machine learning knowledge is required to understand the assumptions made in selecting and training a model. On the other, domain knowledge lets the experimenter know which assumptions are actually warranted by biology and which are inappropriate.

A lot of interesting science is done at the intersection of these two domains. That being said, I frequently read papers that would be amazing, but the authors make mistakes because their expertise is skewed towards one field or the other.

The goal of this article is to describe some of the small experimental design details that are critical in Bio ML papers. Equipped with this knowledge you can read these papers more carefully and notice strengths or flaws you might otherwise have missed.

Data Splitting

In machine learning the standard way to evaluate model performance is to randomly split your data into three sets known as the train, validation, and test set. A model’s performance on each dataset tells you something different about it. The training set is the data the model is actually fit to, and the training set performance tells you how far training has progressed.

The validation set is the data not used in training the model. When training multiple models, or a single model with different hyperparameters, the models’ performance on the validation set tells you which model to actually use.

Finally, the test set is the data held out from the training process. This data can either be pulled randomly from the original dataset, or it can be an external dataset. The important part is that the dataset isn’t used to make any decisions in training or model selection. If that condition holds, then the test set performance is an estimate of how well a model should perform on new data.

Failures of Data Splitting in Biology

Interestingly, determining the train/test/validation sets by randomly selecting samples from the whole dataset often fails in biology. As stated previously, the separation between the training, validation, and testing data is what allows them to be useful estimators. If you split data at the per-sample level in biology, however, you’ll end up leaking data between those sets.

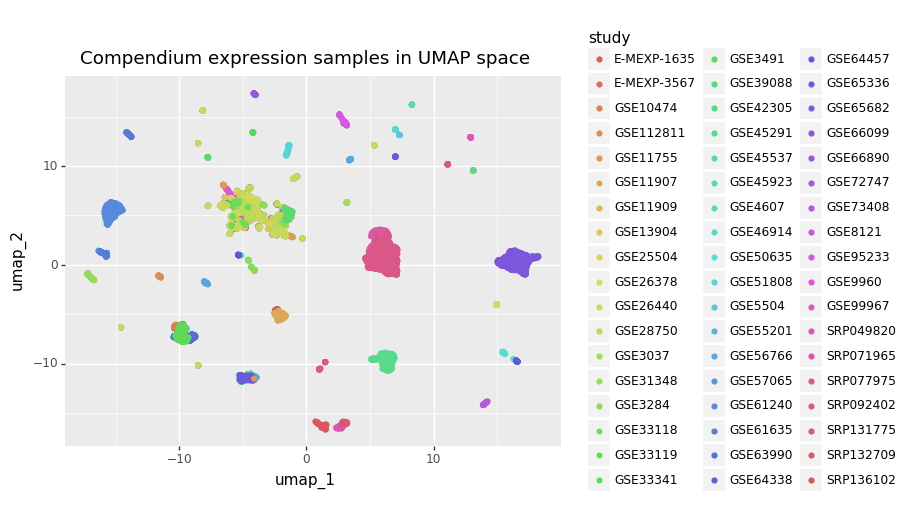

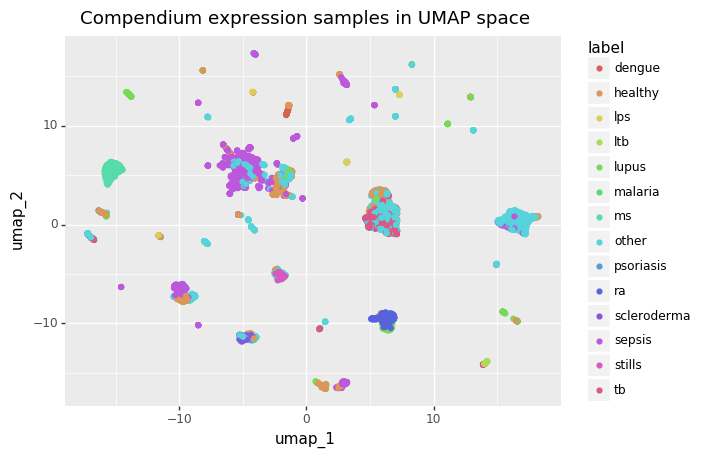

For example, I work with gene expression data, where batch effects are very pronounced. These batch effects are strong enough that the healthy and disease states from the same study look more similar to each other than healthy gene expression across studies (see images below).

Imagine if I were to split the data by randomly assigning samples into train, validation, and test sets without regard for which study they came from. Any model I trained would have a good idea of what the data in the test set looked like based only on the training data. Then, when the model was applied to studies outside the original data, it would take a huge performance hit because it wouldn’t know anything about their studies. The whole issue can be avoided, though, by assigning data into splits at the study level instead of the sample level.

Data Leakage

In machine learning, the term of art for problems like the one in the previous section is “data leakage”. Data leakage occurs when the training set gives the model information about the testing set that the model won’t have when applied to new data. There are a number of ways in which data leakage can happen. One common failure mode in biology is to perform preprocessing on all data jointly instead of on the training and testing data. For a more in depth description, Jacob Schreiber gives a great explanation and example in this twitter thread.

IID Assumption

Machine learning makes the (big) assumption that the data used is independently and identically distributed. While this assumption is typically mentioned to point out that the test set should look like the training set, it should also be the case that the test set has the same distribution as the real world data.

That is to say that the claim “based on test set performance, this model should perform well” has the implied caveat “on data that looks a lot like the test set.” As a result, even a properly held-out test set isn’t necessarily a good indicator of a model’s external validity if the test set doesn’t look like the domain it will be applied to.

For example, in gene expression data individual studies have batch effects that make them look different from each other. A test set only containing samples from a single study is likely confounded by batch effects in a way that keeps it from being representative of all gene expression.

Base Rates And Metrics

In statistics, the base rate is the rate at which a class occurs in a population. For problems like disease prediction, the classes of interest have very low base rates in the population. As a result, we can create a model with great accuracy by simply predicting that every case is healthy.

Since “always predict healthy” probably isn’t what you want in a medical decision making tool, accuracy often isn’t the correct metric for evaluating models. Alternatives include balanced accuracy which takes the average accuracy for all classes and F1 score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Also popular are precision-recall curves, which visualize precision/recall tradeoffs. In the case of imbalanced classes, ROC curves should be avoided as they are overly optimistic.

Evaluation with Known Biology

It can be difficult to determine what a machine learning model is learning and what “good performance” actually means. One way to lend credence to a model is to have it make predictions on well understood problems not present in the training/validation sets. For example, if a model is predicting genetic variant pathogenicity, it should probably predict deleterious TP53 mutations as pathogenic.

Comparison to Other Models

Comparison to a baseline model

Complex machine learning models don’t necessarily outperform logistic regression. To justify the decrease in interpretability that comes with a more complex model, papers need to demonstrate that their model performs better than simpler models like logistic regression or random forest.

Comparison to prior work

If other models have been developed to do the same thing, it’s important to show that a new model adds value to the problem. A new model doesn’t necessarily need to be higher performing, but if not it should have some redeeming feature like interpretability, efficiency, or novelty.

Author Degrees of Freedom

When performing comparisons to baseline models or prior work, authors often use models that aren’t theirs without tuning them. While this is fine if they aren’t tuning their own model, if their model is chosen from a set of 50 hyperparameter configurations then the models they are comparing against should also receive similar hyperparameter sweeps.

Reasonable model assumptions

Deep learning models in particular have strong assumptions about the data they’re operating on baked into their architecture. If a paper is using a convolutional neural network, it should be clear why proximity in feature space is important. Likewise, if a paper is using a recurrent neural network, it should be clear why the order of the sequence matters.

Conclusion

Biological data is idiosyncratic, and using it in machine learning models without domain knowledge can lead to mistakes. This article lists things that I think about when reading biology papers using machine learning, but it’s not exhaustive. If you feel like I’m missing something, you’re welcome to DM me on Twitter about it!

Acknowledgements

This post is funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Data-driven Discovery initiative through grant GBMF4552. Thanks to Michael Hoffman for pointing out issues with using ROC curves on imbalanced datasets.

BibTex Citation:

@misc{Heil_2021, title={Evaluating Bio ML Papers - }, url={https://autobencoder.com/2021-01-29-paper-evaluation/}, journal={AutoBenCoding},

author={Heil, Benjamin J.}, year={2021}, month={01}}